It’s Not Ridiculous for Senators to Do Their Job

Contrary to partisan belief, members of congress aren't supposed to be a rubber-stamp for the leader of their party.

A couple days before Pete Hegseth was very narrowly confirmed as our new Defense Secretary, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) signaled that she would be a “no” vote for the Trump nominee.

“After thorough evaluation,” Murkowski said in a statement, “I must conclude that I cannot in good conscience support his nomination for Secretary of Defense. I did not make this decision lightly; I take my constitutional responsibility to provide advice and consent with the utmost seriousness.”

The senator commended Hegseth’s military service, but cited his lack of “experience and expertise,” along with concerns over “accusations of financial mismanagement and problems with the workplace culture he fostered.” She elaborated on character issues she had with Hegseth, including his multiple admitted acts of infidelity and allegations against him of “sexual assault and excessive drinking.”

Murkowski’s decision didn’t come as much of a surprise. Between Hegseth’s immense personal baggage and him sorely lacking the skills necessary for the job, he had been one of Trump’s more controversial nominees. And unlike most Republicans in congress, who assuredly also understood that Pete was a bad fit, Murkowski has never been afraid to say no to Trump and the rest of the GOP establishment. Some may remember that she even voted to convict Trump in his second impeachment.

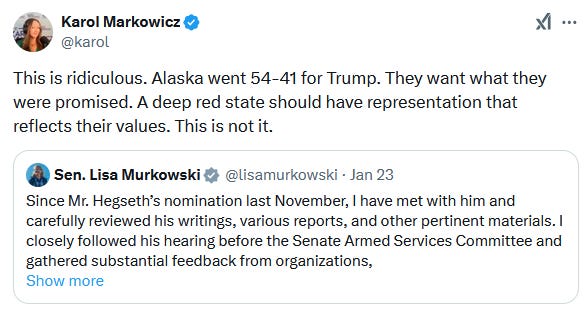

Still, some on the political right, like New York Post and Fox News columnist, Karol Markowicz, found Murkowski’s decision on Hegseth to be outrageous:

While Markowicz’s sentiments were assuredly shared by a whole lot (possibly even millions) of Trump supporters, the notion of a Republican U.S. senator of a red state rejecting a Republican president’s cabinet nominee is by no means “ridiculous.”

It’s not the job, after all, of a senator to blindly do whatever a U.S. president wants. It doesn’t matter if that president belongs to her party, and it doesn’t matter how big of a margin he won her state by. What matters is that in the United States, we live in a system of both representative government and divided government.

A U.S. president has a lot of executive authority (too much, in my view), but it’s not absolute — nor should it be. By constitutional design, we have mechanisms, like the senate confirmation process (which has been around since George Washington’s administration), not for the purpose of hardening or amplifying that authority, but to serve as a check on it.

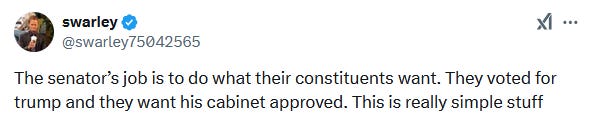

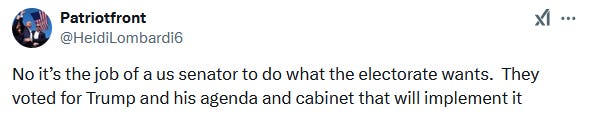

I said as much in an “X” response to Markowicz, which received much more attention than I was expecting. So much, in fact, that I was bombarded with messages like these for two days straight (though most people used more colorful language):

I understand it from an emotional perspective. Trump’s fans adore him. They believe he is entitled (especially after winning back the White House) to get whatever he wants. That, to them, includes all of his cabinet selections. But again, they’re wrong — not just on the civics argument, but likely also in their partisan presumptions.

One of those presumptions was that a majority of Alaskan voters wanted — perhaps even demanded — Pete Hegseth to be the Secretary of Defense. It’s within the realm of possibility, I guess, but where was the data supporting that?

Was Hegseth ever on a ballot in Alaska? Did Trump even mention him as a possible cabinet nominee prior to his November win? Was there any indication at all that Alaskans who did support Hegseth wouldn’t have been just as happy or even happier with a different nominee (perhaps someone with better character who was actually qualified for the job)?

The answer to those questions is no. The same goes for Trump’s other nominees. Thus, insisting that their confirmations were and are the will of the Alaskan people is awfully silly.

Someone who has been on a statewide ballot in Alaska is Lisa Murkowski. Alaskans have elected her four separate times to the U.S. Senate to make senatorial decisions (including on cabinet confirmations) on their behalf.

The second poor presumption was that by voting for Trump last year, a majority of Alaskans handed him a mandate to get every single thing he wants — an outcome Murkowksi therefore has a responsibility to do whatever she can to deliver.

The obvious problem with that premise is that Murkowksi opposed Trump a number of times during his first term as president, after Trump won Alaska by an even larger margin than last November. She did so not only legislatively, but also — as I mentioned earlier — with her conviction vote during his impeachment. Had Trump been convicted, which Murkowski wanted, Trump would have been prevented from ever running for president again.

How did Alaskan voters, who went heavy for Trump in 2016, punish Murkowksi for her treachery? By reelecting her again, just two years ago, over a Republican competitor endorsed by Donald Trump.

You see, voters in Murkowksi’s state are well-aware that she often goes against her party. She’s been doing it, after all, for over 20 years. A lot of people certainly don’t like it; you can sometimes include me among them. But I’m not one of her constituents. The people of Alaska are, and they keep putting her back in office to represent them.

This is why I reject the idea of interpreting the results of a presidential election as a sweeping mandate of… well, really anything. If you disagree, let me take one more stab at convincing you that I’m right…

Contrary to a lot of partisan spin, Trump’s 2024 win was by no means an electoral landslide. It was decisive, but in terms of the electoral college, his margin of victory doesn’t even rank in the top 40 of presidential contests. His popular-vote margin was just 1.5%, making it the smallest since Richard Nixon. And once the counting was completed, we learned that Trump didn’t actually win the popular vote. Most voters (50.2%) voted for someone other than him.

In other words, it was a very close race. Had about 230,000 voters (less than 0.15% of the voting electorate) voted differently across three states, Kamala Harris would be president right now. And I’d be arguing just as strongly that she didn’t have a mandate either.

But forget all of that for a moment, and let’s just look at this from an individual perspective…

I didn’t vote for Trump, but lots of people reading this did. I would ask of those individuals: Do you view your vote as a personal endorsement of literally anything Donald Trump decides to do in office over the next four years? Heck, do you even view it as a endorsement of everything he’s done just within the last week?

For example, did you support him pardoning over 1,500 January 6 criminals, hundreds of whom beat up cops? How about him commuting the sentences of convicted seditionists who were supposed to serve a couple decades in prison, and now, as free men, are vowing retribution against those who put them away? Did you place your seal of approval on Trump’s decision to remove Secret Service protection from former Trump officials (who face legitimate threats of foreign assassination because of the work they did under him)?

Or… did you vote for Donald Trump because you viewed him as the better of two presidential candidates?

If the latter is true (to any degree), you, for entirely justifiable reasons, are not a rubber-stamp for Donald Trump.

Members of congress shouldn’t be one either.

John, I completely agree with your take on all of this. Seems so, so many adults now have a "childish hypocritical" attitude when it comes to adult topics of any seriousness, from politics to child rearing. I'm 63 yrs old, and raised in a more sensible, critical- thinking, and discerning era I suppose. Shocking, these immature adults need their IQ's evaluated, and to start hitting "the books"--- Education is key.

Contrarians in the opposition party are heroic while contrarians in your own party are traitorous.