I've touched on this before, but from the beginning of the pandemic, I've found it frustrating how comfortable a lot of people have been with dismissing the seriousness of COVID-19, based on its relatively high survival rate. Sure enough, the overwhelming majority of people who become infected with the coronavirus do indeed survive it. Globally, that rate is estimated to be a little over 96%, and it’s better here in the United States. And really, the real number is assuredly even better than the estimates, because there's a good number of people who were infected, but either never knew it or never had it diagnosed and therefore reported.

Survivability, of course, is a very good thing. And with the development of better therapeutics, and far more importantly these highly effective vaccines, the end of the health crisis is — knock on wood — quickly approaching.

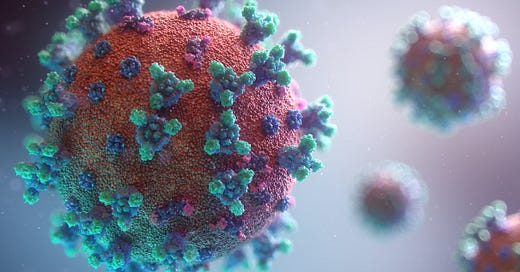

But it's important to take a step back and look at the last 14 months or so, and understand why this virus has been as lethal as it has. The public concern about fatalities should have never been just about a mortality rate, but rather how transmissible the virus is. It’s highly contagious, and has spread across populations in a way that we haven’t seen in a century. The larger the number of infections, the larger the number of deaths.

As of the time I’m writing this, close to 560,000 people have died from it in the United States alone. Again, that’s a small percentage of the total number of Americans who were infected, but the raw number is still devastating. COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in the United States in 2020 (after heart disease and cancer) and increased the total death rate of Americans by 16%.

And that was with local governments and a large number of regular citizens employing mitigation steps and practices that unquestionably saved many lives. I'd argue that many more lives would have been saved if more people had taken simple measures (like social-distancing, avoiding large groups, and mask-wearing when appropriate) more seriously.

Regardless, mortality was never the only serious health concern directly tied to the virus, though it's all a lot of people want to talk about. What about the long-term health of those who got it, and came out on the other end? That number includes tens of millions of Americans.

As best we know, not a single human being had ever been exposed to this disease until 2019. No one on the planet was immune from contracting it and passing it on to someone else. There’s a lot we still don’t know about the virus's susceptibility and long-term effects.

Most of us have probably heard about COVID-19 “long haulers,” of which there are tens of thousands in the United States. They’re the individuals whose recoveries from the infection have dragged on for months and months, impaired by chronic exhaustion, body aches, and mental confusion and strain. Long haulers no longer have the virus in their system, but its lingering effects have made their daily lives extremely difficult and sometimes unmanageable.

We also know about long-term (in some cases permanent) organ damage sometimes caused by the coronavirus, including to the heart and lungs.

Some findings from a very large study recently published in The Lancet Psychiatry are now also cause for concern. The study used health data from over 80 million people worldwide, and concluded that 1 in 3 COVID-19 patients have been diagnosed with a neuropsychiatric condition within six months of contracting the virus. These ranged from mood disorders to even strokes and dementia (the severity of the condition correlating with the severity of the COVID-19 infection).

One standout finding from the study was that individuals had a 44% higher risk of being diagnosed with a neurological disorder after being infected with COVID-19 than after being infected with the flu.

In other words, researchers in the medical community have their work cut out for them. We’ll be learning much more about the after-effects of this virus in the months and years to come.

What’s clear right now, however, is that effectively doing nothing, letting the coronavirus run rampant through populations as if it were a common cold, and relying primarily on natural immune systems to deal with the problem, was always a terrible idea. People who advocated for it (and there were a lot of them) were dead wrong. Logical, reasonable mitigation efforts to reduce infections, hospitalizations, and deaths (not to mention limit mutations of the virus) until vaccines were developed and widely administered, always made sense.

That’s not to say that all mitigation measures have been logical and reasonable. Some absolutely haven’t, and we’ve paid a societal price for them (though in some areas, not as bad as many of us had thought).

But we always should have been (and still should be) mindful of those we live among. This was and is a legitimate health crisis. We knew pretty early on how to help protect those around us with relatively minimal effort and sacrifice, and even that was a bridge too far for a shocking number of people.

The fact that something as simple and non-intrusive as wearing a mask while inside grocery stores turned into a hostile, sometimes violent culture battle (fueled by irresponsible leaders and asinine conspiracy theories) is something I don’t think I’ll ever forget. It's been truly depressing.

As I've told friends, this past year has often felt like an enormous behavioral experiment that people were all too eager to flunk, perhaps just to mess with the conductor.

Again, vaccinations are now here (thank God), and more and more of the population is becoming vaccinated every day. It’s a wonderful thing, and once enough people are vaccinated, practices like social distancing and masking will no longer serve their pandemic-era purpose. They’ll fall by the wayside, and believe me, I won’t miss them.

What I also won’t miss are the daily reminders of how little some people are concerned with the well-being of others in times of crisis.

Note from John: I've been writing a weekly non-political newsletter since October, covering topics like art, music, humor, travel, society and culture. I've been surprised by, and thankful for, how many people have been signing up for it. If it sounds interesting to you, I'd love for you to subscribe (it's free).